- Home

- Jonathan Stroud

The Outlaws Scarlett and Browne Page 8

The Outlaws Scarlett and Browne Read online

Page 8

Frowning, she watched him totter to his feet. She watched him brush a few gray chunks of river mud off first one leg, then the other. He straightened. Before she could speak, he bent again and methodically picked a twist of riverweed from the laces of one shoe.

She glared at him. “Finished?”

“Yes. No, wait—there’s another bit of weed here too.”

“Forget the weed. Listen to me. Who were those men?”

“Which men?”

Scarlett gave a hiss, lurched close, and grappled him around the collar. “You know which men! The ones who tried to kill us! The ones who we barely escaped by leaping off a cliff! The ones who put a knife through my hand!”

He blinked at her, his eyes pools of innocence and woe. “Your poor hand. How’s it doing?”

She held up her blackened claw. A crust as dark as burned sugar bloomed like a ragged flower across the palm, while fresh bloody stalks ran down her wrist and up her sleeve.

“How do you think it’s doing, Albert?”

He peered at it. “Ooh. Ah. Is it sore?”

“You can see daylight through the center! Yes, it’s sore!” She glared at him. “And it’s your fault! Answer my question, you little mud-rat, or I’ll knock you down.”

The boy spoke carefully. “I don’t think you should punch anything with that bad hand.”

“I won’t. I’m ambidextrous. I’ll use the other one.” She raised her fist. “In precisely two seconds.”

“But I don’t know who those men were! I’ve never seen them before!…Ow!”

“That was just a slap. There’s more to come.”

“But I swear I’ve never—”

“I’m not asking for their middle names and birthdays! I want to know why they’re after you! For what purpose! And that, my friend, you most certainly do know. Speak!”

Albert Browne made a frantic defensive gesture. He took a step back, and then another, slipping and sliding on the black shingle.

“I don’t know! Perhaps…perhaps they were from Stonemoor.”

“That doesn’t mean anything to me. What is ‘Stonemoor’? Keep talking.”

“It is where I lived. A great gray house…” His eyes flitted toward her and away again. “Do not send me back there, Scarlett. If you try, I will walk into the river and drown myself. Do not send me back there.”

“I’m not going to send you back. Shiva’s ghost! I don’t even know where it is. Was it in Gloucester? Cheltenham? Someplace like that?” She waited, but he looked at her in bafflement; clearly the names meant nothing to him. Scarlett rubbed in frustration at the side of her face. “Was it even in a town?”

“I do not know.”

“But you know what a town is?”

He smiled broadly. “You mean a place with standing buildings, shops, a surrounding wall, gates, and defenses to keep out the Tainted and other beasts. There are people in it.”

“Yes. That is a town. Gods above us. And Stonemoor?”

Albert nodded. “I do not know if it was in such a place. We never left it. Beyond the house were the grounds, and beyond the grounds a long high wall, and when I stood at the windows I could not see past the wall, except for the green tops of trees far away.”

Perhaps he wasn’t actually lying, but he was not telling the whole truth, of that Scarlett was sure. He had left to get on the bus, for one thing. She scowled, screwing up her eyes. His unworldliness wasn’t faked, she was certain of that; naïveté rolled off him like mists from a mountaintop. But there was more to him than this. Dangerous people wanted him dead.

“Tell me about this house,” she said. “Who lived there?”

“It was me, Old Michael”—he hesitated—“and Dr. Calloway….”

“Just three people?”

“Oh, well, there were the other guests, and the servants, and the medics and technicians, and there were the guards who stood at the doors, and the ones who walked in the grounds shooting the birds if they flew too close, and there were the odd-jobbers, and the boy with the quiff who died, and some others I forget. I was not allowed to speak with any of them, apart from answering specific questions. If I did, Dr. Calloway whipped me.” He took a breath. “But now she is in the past, and Old Michael is dead, and I don’t like to think of any of it more than I can help.” He smiled at her, as if that finished the matter. “Scarlett, are you all right?”

Scarlett in fact felt sick and dazed. The sky shone white like a sheet of iron. Her hand hurt. It was hard to focus.

“So you were kept locked up in this house?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“Why?”

The smile on his face grew fixed and taut. He did not look at her. “No one ever told me.”

“Got to be a reason, Albert, and I think you know it. But then you escaped, did you?”

“I found an open door. I went out. I wanted to see the world.”

“I see. As easy as that. And what happened on the bus?”

“The bus?”

“Why did it crash, Albert?”

“You know, you do look awfully pale, Scarlett. Do you want to sit down?”

“No! I want an answer to my question.”

“The driver lost control. It all happened so fast. I find it hard to recall.”

Scarlett took a slow breath, wondering whether to slap him again. Her cold, wet clothes clung to her, and she could feel an ache behind her eyes. No, now was not the time. “Shame,” she said, stepping away. “Us being two comrades and all. It’s a crying shame you can’t be straight with me.”

“That insinuation rather hurts,” the boy said. “I have told you many interesting and truthful things. Also…if it’s a question of being straight with one another, I must say for a ‘simple pilgrim and a girl of God,’ you seem very skilled at shooting people through the head.”

Scarlett shrugged. “I’m a multitasker, what can I say? All right, don’t tell me. But if your Dr. Calloway ever catches up with us, I might see if I can get a proper answer out of her.”

She turned to get her bag—but before she knew it, Albert was at her side. She had never seen him move so fast. A fierce urgency possessed him; his eyes were wide and staring. “Scarlett, please do not speak so casually of that woman! She is perilous. I have seen her do terrible deeds!”

“Yeah?” Scarlett hesitated, momentarily taken aback. “I’ve done stuff too.”

His voice dropped to a whisper. “If she should ever find us,” he said, “you must run from her and keep running. Do not seek shelter; she will find you. Do not try to parley; she will cut you down. Do not fight back; she will laugh in your face as you spin and burn. Remember, it is death to go near her! Death!” He gave a final shudder; his face went bland and calm again. “But she seldom leaves Stonemoor, I am glad to say, so I’m sure it will never happen. Now, Scarlett—it is time to rejoice in the present. What do you want us to do?”

Scarlett was thinking of the black outline she had seen on the cliff top as the river had swept them away. A woman’s shape, watching them go. She said: “We must get to a town. I need to fix my hand. And that means a long walk.”

The boy looked at her, aghast. “Another walk? But I’m so tired, Scarlett.”

“Me too, and if we stay here, the storks will pick at our bones. We’re miles from anywhere. We’ll have to cut our way through the reeds and bogs, fight off river snakes, walk till our feet bleed. Walk till we reach a town. Otherwise we die. You understand me, Albert? We’ve got no other option.”

“True. Unless we take the boat.”

Scarlett blinked at him; she slowly turned her head. As in a dream, she looked where he was pointing. Sure enough, just beyond the bridge, tucked among the reeds and willows, a battered rowboat was tethered to a post.

“How about you walk, I take the boat,” Albert

said. “That option works well too.”

But Scarlett was already ahead of him, pushing through the reeds, stumbling in the mud, ignoring the clattering outcry of the storks as she waded past the concrete supports. Her heart was beating fast. A boat! What luck! They could float to a river town, where medics—

“And look,” Albert said, “there’s the owner.”

Not far beyond the bridge, the reeds had been cut away. A tumbledown hut stood in the dappled shadows of the willow trees. Old sulfur sticks hung black and waxy among the fronds, and rangy chickens scrabbled here and there in the scratty soil. Beside the riverbank, hunched on an ancient dining chair and doing something uncoordinated with a fishing rod, sat a very large man. He wore a straw hat with a ragged brim, a pair of faded jeans, and a blue checked shirt hanging open over a stained white T-shirt. His feet were bare. He was gray-haired, voluminously bearded, and powerfully built. A beetling brow, protruding over a veiny nose, cast into deep shade two small and cunning eyes set slightly too close together. Scarlett saw at once he was a classic backwoodsman of a kind commonly found in the Oxford Sours.

The man had been alerted by the clamor of the storks. As they emerged from the shadow of the bridge, he let out a grunt of aggression and surprise. Flinging down the fishing rod, he got to his feet and set off purposefully toward them, kicking a chicken out of his way.

At Scarlett’s side, Albert hesitated. “Maybe we should walk after all.”

Scarlett looked at the man. Although not young, he was taller than she was by a full foot, maybe more, and broader than the two of them put together. He had an enormous jagged hunting knife tucked in his dirty string belt. He had sized up Albert in a moment and was now staring at Scarlett with a keen interest that bordered on wolfish rapacity.

“He will want money for the boat,” Albert whispered. “You do have money, don’t you, Scarlett? Please say you do. Or what can you give him in exchange?”

Scarlett pursed her lips thinly. As of the last few hours, she had rather less money than she cared to contemplate. “Don’t worry,” she said. “I’ll give him something.”

The man stepped close and opened his mouth to speak. As he did so, Scarlett swayed forward and punched him full in the face with all the strength of her good hand, so that his head jerked back and he toppled to the earth like a felled tree. He lay spread-eagled, toothless mouth agape, eyes closed, fingers twitching, his unkempt beard jutting to the skies.

Albert Browne had given a cry as the blow struck. “That poor old man!”

Scarlett gazed at him. “Are you blind? He was clearly a git. And we need his boat. He would not have given it to us otherwise.”

“You didn’t even ask him!”

“There was no point. Stop gawping. Hurry up and get aboard.”

Albert shook his head in wonder. “Your behavior surprises me. What next? Are you going to kick him while he’s down? Why not rob the fellow too?”

There was a pause. “You know,” Scarlett said slowly, “that last one is an excellent idea.”

Albert and Scarlett did not speak much during their onward journey in the little rowboat. Mostly this was because they were busy devouring the supplies they had found in the bearded woodsman’s hut. There was smoked fish and black rye bread, bags of apples, onions, and hazelnuts, and plastic bottles of a watery beer, which they sipped from metal pannikins. The bread was stale, but the fish and beer were very good. They sat facing each other, knees almost touching, eating and drinking with fanatical intensity and staring determinedly in opposite directions.

Albert was still slightly affronted by the robbery they had committed, but not enough to ignore the food. It was the best meal he had ever tasted. When he was finally full to bursting, he wiped his mouth on the sleeve of his jumper and belched contentedly. Then he settled back to read Scarlett’s mind and watch the world drift by.

The landscape was changing, the reeds and marshes being replaced by meadows. They were entering the safe-lands around a settlement, though the Wilds were still at hand. At a bend in the river, a great brown otter, as long as a man, sunned itself on the mud, belly up, tail trailing in the water, following the progress of the boat with black, unblinking eyes. Beasts that size could easily kill a child—drag it to the cool green depths of the river and wedge it amongst the tree roots for devouring later. But for Albert Browne the bright day bleached away the horror; he marveled at the light playing on the rich and creamy fur, and the boat passed swiftly on.

Albert had long wanted to see such things. He had lain in his cell as the rattle of the pill carts sounded down the corridor and dreamed of animals, forests, and towns, and the Free Isles sparkling far away. Now he was experiencing it all. Yes, his enemies would keep pursuing him, and he would not be safe forever. But the sun was shining, he had a decent start, and he felt no trace of the Fear inside him. Even better, he had Scarlett at his side.

Scarlett! So much of his good fortune was down to her. Yes, she might be a bit grumpy with him right now, but she’d saved his life several times, and no amount of slapping or eye rolling could change that. When she wasn’t looking, he snatched little glances at her, noting how—despite her battered clothes and bloodied hand—she sat straight-backed, perfectly balanced and erect of purpose, watching the way ahead. Strands of her long auburn hair whipped about her bone-pale face, which showed precisely the same fierce and freckled poise that had transfixed him from the moment he’d fallen out of the toilet at her feet. Nothing in the muffled, muted corridors of Stonemoor had prepared him for Scarlett McCain’s existence, and it overwhelmed Albert to realize they had been thrown together only by chance. How easily he might have missed her! If he had chosen to leave the wrecked bus earlier, perhaps, or if she had taken another way through the forest…The awful notion didn’t bear thinking about at all.

Not that she was easy company. She hadn’t said a word to him since getting into the boat. The reasons were obvious, and he didn’t actually need to read her mind to understand her silence. But really it was impossible not to, her sitting so close like that, and with her thoughts breaking over him in hot clouds of indignation, suspicion, and pain.

Her wound was distressing her, and she blamed him for it. That was the strongest emotion by far. But she also had images of banknotes swirling in her head, and when these came into focus, her annoyance with him grew particularly sharp—Albert didn’t know quite why. On top of all that, a great angry curiosity burned inside her about him and his past. For some reason, she was cross with him about this, too; cross even with herself for being curious. It was all a bit of a mess, in Albert’s opinion, as other people’s heads so often were. Still, no doubt she would calm down in time.

“Albert, stop daydreaming!” Her voice made him jump. “We’re getting near.”

He swiveled on his bench. The river was running through a patchwork expanse of fields, with crops growing green and orange in the westering sun. To his fascination, Albert saw a battered tractor moving slowly up a rutted lane. Somewhere ahead, twists of chimney smoke rose blue into the eggshell air.

He felt a thrill of eagerness and fear.

“Oh, Scarlett,” he said, “I could shake you firmly by the hand. Not your bad hand, obviously—that would be a mistake. But to visit an actual town…that has long been one of my heart’s desires! Will there be inns and cake shops there?”

She gazed at him. “Yes. More to the point, it will have doctors. I assume you don’t have any cash?”

“None.” He said it sadly; he would have liked to please her. His eyes flicked to her rucksack. “I’m sorry that you’ve lost your money too.”

For some reason, that was a mistake. A bulb of rage flared round her, a halo of exasperated light. She swore under her breath. Slowly, glaring at him, she located a penny in her pocket and transferred it to the leather box at her neck. “How do you know that?” she asked. “As it happens, you’

re right. I still have a few quid, but the doctors will take it all….” Her frown deepened. “You’re staring at me. What are you doing that for?”

Albert smiled politely. “It’s just I notice you put coins in that little box whenever you use rude words. I was wondering why, that’s all.”

The halo faded. Scarlett sighed. “It is an imperfect world,” she said. “I am imperfect. The cuss-box is there to remind me of that fact. When I fall short of the standards I expect of myself, I slip a coin inside. The weight reminds me to do better.”

Albert nodded in understanding. “I see. Yes, you kill, you lie, you rob, you hit old men and steal their boats. I only thank the gods you draw the line at swearing—it would have been just too dreadful otherwise. What do you do with the money?”

“None of your business. But look now—there’s the town.”

The river had swept around a bend and flowed due south, straight between the fields, and in the distance rose a high earth wall, with colored flags upon it. A crowd of rooftops peeped beyond, a spire, two brick-and-concrete towers, a host of smoking chimneys. Even at a distance, Albert could see a great gate, bright and shining, set open in the wall. There were grassy dikes either side of the river, with stone paths atop them, and many people walking, carrying the tools with which they’d been working in the fields. Boats with triangular sails moved upon the river—white notched flecks that caught the sun, drifting lazily to and fro.

The scene was on a different scale from anything Albert had imagined.

“It’s so big…,” he said. “So magnificent…. Tell me, what is that spiky tower thing?”

She scowled. “The Faith House, at a guess.”

“And that ornate roof to the left?”

“The top of a cricket pavilion.”

“Amazing…. How many people live there?”

Scarlett shrugged. “Several thousand. It’s one of the Surviving Towns of Wessex. Lechlade, at a guess—I came here years ago.” She sniffed disparagingly. “A word of warning, Albert, before you start gibbering with anticipation. Don’t be misled by all the flags and finery. Towns aren’t more civilized than the Wilds. In some ways, they’re worse. See the black things on the battlements? That’s cannon for shooting outsiders like you and me. They’ll do that if we’ve got the plague, if we’re deformed, if we’re outlaws, or if they think we’re in the pay of the Welsh. Supposing they let us in, the same applies. They’re desperate to keep the old ways going. The High Council of the Faith Houses is on the watch for any kind of deviation, be it physical or moral, and if they find it, they’ll kill us in short order. And the population will help them. It’s been like that for at least a hundred years, and they aren’t going to change their habits on account of ragged-looking visitors like us.” Her eyes narrowed. “Particularly if we’ve got secrets to hide.”

The Leap

The Leap Buried Fire

Buried Fire Heroes of the Valley

Heroes of the Valley The Empty Grave

The Empty Grave The Hollow Boy

The Hollow Boy The Last Siege

The Last Siege The Dagger in the Desk

The Dagger in the Desk The Amulet of Samarkand

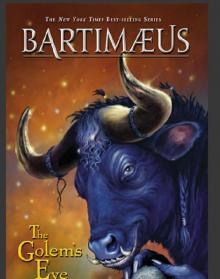

The Amulet of Samarkand The Golem's Eye

The Golem's Eye The Screaming Staircase

The Screaming Staircase The Outlaws Scarlett and Browne

The Outlaws Scarlett and Browne The Ring of Solomon: A Bartimaeus Novel

The Ring of Solomon: A Bartimaeus Novel Lockwood & Co

Lockwood & Co Lockwood & Co: The Screaming Staircase

Lockwood & Co: The Screaming Staircase Bartimaeus: The Amulet of Samarkand

Bartimaeus: The Amulet of Samarkand The Amulet of Samarkand tbt-1

The Amulet of Samarkand tbt-1 Lockwood & Co.: The Creeping Shadow

Lockwood & Co.: The Creeping Shadow The Ring of Solomon

The Ring of Solomon Lockwood & Co. Book Three: The Hollow Boy

Lockwood & Co. Book Three: The Hollow Boy Bartimaeus: The Golem’s Eye

Bartimaeus: The Golem’s Eye