- Home

- Jonathan Stroud

The Ring of Solomon Page 8

The Ring of Solomon Read online

Page 8

First off, we were both djinn of high repute and ancient origin, although (typically) Faquarl insisted his origin was a little more ancient than mine.1

Secondly, we were both zestful individuals, potent, resourceful and good in a scrap, and formidable opponents of our human masters. Between us we had accounted for a great many magicians who had failed to close their pentacles properly, misspoken a word during our summonings, left a loophole in the terms and conditions of our indentures, or otherwise messed up the dangerous process of bringing us to Earth. The flaw in our feistiness, however, was that competent magicians, recognizing our qualities and wishing to use them for their own ends, summoned us ever more frequently. The net result was that Faquarl and I were the two hardest-working spirits of that millennium, at least in our opinion.

If all that wasn’t enough, we had plenty of shared interests too, notably architecture, politics and regional cuisine.2 So one way and another you’d have thought that Faquarl and I would have got along fine.

Instead, for some reason, we got up each other’s noses,3 and always had done.

Still, we were generally prepared to put our differences aside when faced with a mutual enemy, and our present master certainly fitted that bill. Any magician capable of summoning eight djinn at once was clearly a formidable proposition, and the essence-flail didn’t make things any easier. But I felt there was something more to him even than that.

‘There’s one odd thing about Khaba,’ I said suddenly. ‘Have you noticed—?’

Faquarl gave me a sharp nudge; he tilted his head slightly. Two of our fellow workers, Xoxen and Tivoc, had appeared down the quarry path. Both were trudging wearily and rested spades upon their shoulders.

‘Faquarl! Bartimaeus!’ Xoxen was incredulous. ‘What are you doing?’

Tivoc’s eyes gleamed nastily. ‘They’re having a breather.’

‘Come and join us if you want,’ I said.

Xoxen leaned upon his spade and wiped his face with a dirty hand. ‘You fools!’ he hissed. ‘Don’t you remember the name and nature of our master? He is not called Khaba the Cruel because of the fond generosity he shows to skiving spirits! He ordered us to work without breaks during the hours of light. By day we toil, by night we rest! What is there in this concept that you don’t understand?’

‘You’ll have us all in the essence-cages,’ Tivoc snarled.

Faquarl made a dismissive motion. ‘The Egyptian is just a human, imprisoned in grim flesh, while we are noble spirits – I’m using the term “noble” in the loosest possible sense, of course, so as to include Bartimaeus. Why should any of us toil for Khaba? We should work together to destroy him!’

‘Big talk,’ growled Tivoc, ‘but I notice the magician is nowhere in sight.’

Xoxen nodded. ‘Exactly. When he appears, you’ll both be chiselling at double speed, you mark my words. In the meantime, shall we report that your first blocks are not quite done? Let us know when they’re ready to be dragged up to the site.’

Wheeling round, they minced out of the quarry. Faquarl and I stared after them.

‘Our workmates leave much to be desired,’ I grunted. ‘No backbone.’4

Faquarl picked up his tools and rose heavily to his feet. ‘Well, we’re just as bad as them so far,’ he said. ‘We’ve been letting Khaba push us around too. The trouble is, I don’t see how we’re going to fight back. He’s strong, he’s vindictive, he’s got that cursed flail – and he’s also got …’

His voice trailed off. We looked at each other. Then Faquarl sent out a small Pulse that expanded around us, creating a glowing, green Bulb of Silence. The few faint noises from the hill above, where the spades of our fellow djinn could distantly be heard, became instantly muffled; we were alone, our voices insulated from the world.

Even so, I leaned in close. ‘Have you noticed his shadow?’

‘Slightly darker than it ought to be?’ Faquarl muttered. ‘Ever so slightly longer? Responds just a little too slowly when Khaba moves?’

‘That’s the one.’

He made a face. ‘Nothing shows on any of the planes, which means a very high-level Veil’s in place. But it’s something all right – something protecting Khaba. If we’re going to get him, we first need to find out what.’

‘Let’s keep an eye on it,’ I said. ‘Sooner or later, it’ll give itself away.’

Faquarl nodded. He flourished the chisel; the Bulb of Silence burst into a scattered shower of emerald droplets. Without another word, we went back to our work.

For a couple of days activities proceeded quietly at the temple site. The top of the hill was levelled, scrub and brushwood were cleared away, and foundations for the building were dug. Down in the quarry Faquarl and I produced a good number of top-quality limestone blocks, geometric, symmetrical, and so cleanly finished the king himself could have eaten his breakfast off them. Even so, they didn’t meet with the approval of Khaba’s odious little overseer Gezeri, who materialized on an outcrop above our heads and tuttingly inspected our work.

‘This is poor stuff, boys,’ he said, shaking his fat green head. ‘Lots of rough bits down the sides need sanding. The boss won’t accept ’em like that, oh dear me, no.’

‘Come closer and show me exactly where,’ I said pleasantly. ‘My eyesight isn’t what it was.’

The foliot hopped down from the ledge and sauntered over. ‘You djinn are all the same. Big bloated sacks of uselessness, I call you. If I was your master, I’d riddle you with a Pestilence each day just on princip— Ay!’ Further such pearls of wisdom from Gezeri were in short supply for the next few minutes, as I industriously sanded down the edges of the blocks using the side of his head. When I’d finished, the blocks gleamed like a baby’s bottom, and Gezeri’s face was flattened like an anvil.

‘You were right,’ I said. ‘They look much better now. So do you, as a matter of fact.’

The foliot pranced from foot to foot with fury. ‘How dare you! I’ll tell on you, I will! Khaba’s got his eye on you already! He’s just waiting for an excuse to plunge you in the Dismal Flame! When I go up and tell him—’

‘Here, let me help you out with that.’ In a philanthropic spirit, I grabbed him, tied his arms and legs in a complex knot, and with an impressive kick punted him high over the quarry walls to land somewhere on the building site. There was a distant squeak.

Faquarl had been watching all this with urbane amusement. ‘Bit reckless, Bartimaeus.’

‘I get the flail daily anyway,’ I growled. ‘Once more won’t make any difference.’

But in fact the magician seemed too preoccupied now even to do much scouring. He spent most of his time in a tent on the edge of the site, checking the building plans and dealing with messenger-imps sent from the palace. These messages carried endless new instructions for the temple layout – brass pillars here, cedar floors there – which Khaba had to instantly incorporate into the plans. Often he came out to double-check his changes against the work that had been done so far, so whenever I was up dragging a block onto the site, I took my chance to study him.

It wasn’t very reassuring.

The first thing I spotted was that Khaba’s shadow was always at his heels, trailing behind him along the dirt of the ground. It remained there regardless of the position of the sun: never in front, never to the side, always quietly behind him. The second thing was even odder. The magician seldom emerged when the sun was at its zenith,5 but when he did, it was noticeable that while all other shadows were reduced almost to nothing, his was still long and sleek, a thing of evening or early morning.

Though it more or less corresponded to its owner’s shape, it did so in an elongated sort of way, and I took an especial dislike to its long, thin, tapering arms and fingers. Usually these moved in conjunction with the movements of the magician, but not always. Once, as I was helping push a block towards the temple, Khaba observed us from the side. And out of the corner of my eye I seemed to see that, though the magician had his arms crossed, his shadow’s a

rms now resembled those of a praying mantis, folded hungrily and waiting. I turned my head swiftly, only to find the shadow’s arms crossed normally, just as they should have been.

As Faquarl had observed, the shadow looked the same on each of the seven planes, and this was ominous in itself. I’m no imp or foliot, but a strapping djinni with full command of every plane, and ordinarily I expect to be able to see through most magical deceptions going. Illusions, Concealments, Glamours, Veils, you name it – by flipping to the seventh plane they all disintegrate before my eyes into obvious layers of glowing wisps and threads, so that I see the true thing beneath. It’s the same with spirit guises: show me a sweet little choirboy or a smiling mother and I’ll show you the hideous fanged strigoï6 it really is.7 There’s very little that remains hidden from my sight.

Not with this shadow. I couldn’t see past its Veil at all.

Faquarl didn’t have any better luck, as he confided one evening by the campfire. ‘It’s got to be high level,’ he muttered. ‘Something that can fox us on the seventh isn’t going to be a djinni, is it? I think Khaba’s brought it with him from Egypt. Any idea what it could be, Bartimaeus? You’ve spent more time there than I have lately.’

I shrugged. ‘The catacombs at Karnak are deep. I never got far in. We need to tread cautiously.’

Just how cautiously was brought home to me the following day. There was a problem with the alignment of the temple porch, and I’d shinned up a ladder to assess things from above. I was concealed in a narrow cleft between two blocks, and was fiddling with my cubit rod and plumb line, when I saw the magician pass by me on the hard tamped earth below. A small messenger-imp approached from the direction of the palace, a missive in its paw, and intercepted him; the magician halted, took the wax tablet on which the message was impressed, and read it swiftly. As he did so, his shadow, as was its wont, was stretched out long on the ground behind him, though the sun was almost at its height. The magician nodded, tucked the tablet in a belt-pouch and proceeded on his way; the imp, with the aimless vapidity of its kind, meandered off in the opposite direction, picking its nose the while. In so doing it passed the shadow; all in an instant there was a blur of movement, a single sharp snapping noise, and the imp was gone. The shadow flowed away after the magician; just as it disappeared from view, its trailing head turned to look at me, and in that moment it didn’t seem the least bit human.

With slightly shaking hands, I completed my measurements and descended stiffly from the porch. All things considered, it was probably best to keep away from the magician Khaba. I would lie low, do my jobs effectively, and above all not draw attention to myself. That would be the best way to keep out of trouble.

I managed it for four whole days. Then disaster struck.

1 By his account, Faquarl’s first summoning was in Jericho, 3015 BC, approximately five years before my initial appearance in Ur. This made him, allegedly, the ‘senior’ djinni in our partnership. However, since Faquarl also swore blind he’d invented hieroglyphs by ‘doodling with a stick in the Nile river-mud’ and claimed to have devised the abacus by impaling two dozen imps along the branches of an Asiatic cedar, I regarded all his stories with a certain scepticism.

2 In my view the people of Babylonia were the tastiest, owing to the rich goat’s milk in their diet. Faquarl preferred a good Indian.

3 Or snouts. Or trunks. Or tentacles, filaments, palpi or antennae, depending which guise we were in.

4 To be fair, a few of them were all right. Nimshik had spent a good while in Canaan and had interesting points to make about the local tribal politics; Menes, a youngish djinni, listened attentively to my words of wisdom; even Chosroes grilled a mean imp. But the rest were sorry wastes of essence, Beyzer being boastful, Tivoc sarcastic and Xoxen full of false modesty, which in my humble opinion are three immensely tiresome traits.

5 He preferred to keep to his tent and let foliots in the shape of Scythian slave boys wave palms above his head and feed him sweetmeats and iced fruit. Which I suppose is fair enough.

6Strigoï: a disreputable sub-class of djinni, pallid and nocturnal, with a predilection for drinking the blood of the living. Think succubus, but without the curves.

7 Not always. Just sometimes. Your mother is absolutely fine, for instance. Probably.

10

The port of Eilat came as a surprise to Asmira, whose experience of cities was limited to Marib and its sister town of Sirwah thirty miles away across the fields. Crowded as they often were, especially on festival days, they maintained at all times a certain order. The priestesses wore their golden kirtles, the townsfolk their simple tunics of white and blue. If men from the hill-tribes were present, their longer robes of red and brown made them easily identifiable from the guard posts. With the single cast of an eye a guard could appraise a crowd, and assess the dangers within.

In Eilat, it was not so simple.

Its streets were broad and the buildings never higher than two storeys. To Asmira, used to the calm, cool shadows of Sheba’s towers, this made the city oddly formless, a hot and sprawling mass of low whitewashed walls that merged disconcertingly with the ceaseless tide of people that passed among them. Richly garbed Egyptians stalked along, amulets gleaming upon their breasts; behind came slaves carrying boxes, chests, scowling imps in swinging cages. Wiry men of Punt, bright-eyed, diminutive, with sacks of resin teetering on their backs, wound their way past stalls where Kushite merchants offered silver djinn-guards and spirit-charmers to the wary traveller. Black-eyed Babylonians argued with pale-skinned men over carts of strangely patterned pelts and skins; Asmira even spotted a group of fellow Shebans come north on the gruelling frankincense trail.

Up on the rooftops, silent things wearing the shapes of cats and birds watched the activity unfold.

Asmira, standing at the gates, wrinkled her nose with distaste at the unregulated magic of the magician-king’s domain. She bought spiced lentils from a kiosk set into the city wall, then plunged into the throng. Its turbid flow engulfed her; she was swallowed by the crowd.

Even so, she knew she was being followed before she had walked a dozen yards.

Chancing to glance back, she noticed a thin man in a long pale robe detach himself from the wall where he had been leaning and move after her along the road. A little later, after two random changes of direction, she looked again and found him still in sight, dawdling along, staring at his feet, seemingly entranced by the clouds of dust he kicked up with every casual step.

An agent of Solomon already? It seemed unlikely; she had done nothing to draw attention to herself. Unhurriedly Asmira crossed the street under the white heat of the day and ducked beneath the awning of a bread-seller. She stood above the baskets in the hot shade, breathing in the scent of the piled loaves. Out of the corner of her eye she saw a pale flash move amongst the customers at the fish stall alongside.

An old and wrinkled man sat hunched between the bread baskets, chewing toothlessly on his khat. Asmira purchased a thin wheat loaf from him, then said: ‘Sir, I need to travel to Jerusalem as a matter of urgency. What is the quickest way?’

The old man frowned; her Arabic was strange to him, and barely intelligible. ‘By camel train.’

‘Where do the camels leave from?’

‘From the market square beside the fountains.’

‘I see. Where is the square?’

He pondered long, his jaw moving in slow, circular movements. At last he spoke. ‘Beside the fountains.’

Asmira’s brow furrowed, her bottom lip protruded in vexation. She glanced back towards the fish stall. ‘I’m from the south,’ she said. ‘I don’t know the town. Is camel train really the quickest way? I thought perhaps—’

‘Are you travelling alone?’ the old man said.

‘Yes.’

‘Ah.’ He opened his gummy mouth and emitted a brief chuckle.

Asmira gazed at him. ‘What?’

Bony shoulders shrugged. ‘You’re young, and – if the shadows of y

our shawl don’t conceal unpleasant surprises – good looking too. Plus you’re travelling alone. In my experience, your chances of leaving Eilat safely, let alone reaching Jerusalem, are slim. Still, while you yet have life and money, you might as well spend freely; that’s my philosophy. Why not buy another loaf?’

‘No, thank you. I was asking about Jerusalem.’

The old man stared at her appraisingly. ‘The slavers here do very well,’ he mused. ‘I sometimes wish I’d gone into that trade …’ He licked a finger, stretched out a hairy arm and adjusted the display of flatbread in a nearby basket. ‘Ways to get to Jerusalem? If you were a magician, you could fly there on a carpet … That’s quicker than camels.’

‘I’m not a magician,’ Asmira said. She adjusted the leather bag across her shoulder.

The old man grunted. ‘That’s lucky, because if you flew to Jerusalem on a carpet, he’d see you by way of the Ring. Then you’d be taken by a demon and carried off, and subjected to all sorts of horrors. Sure I can’t interest you in a pretzel?’

Asmira cleared her throat. ‘I thought perhaps a chariot.’

‘Chariots are for queens,’ the bread-seller said. He laughed, his mouth gaping like a void. ‘And magicians.’

‘I’m neither,’ Asmira said.

She took up her bread and left. A moment later a thin man wearing a pale robe pushed aside the customers of the fish stall and slipped out into the day.

The beggar had been working his patch outside the bazaar since dawn, when the tide had brought new ships into Eilat’s quays. As always the merchants had heavy purses tied at their belts, which the beggar attempted to lighten in two complementary ways. His roars and pleas and pitiful exhortations, together with the proud display of his withered stump, always awoke sufficient revulsion to earn some shekels from the crowd. Meanwhile his imp, loitering amongst the bystanders, picked as many pockets as it could. The sun was hot and the business good, and the beggar was just thinking of departing to the wine shop when he was approached by a thin man wearing a long pale robe. The newcomer scuffled to a halt, staring at his feet.

The Leap

The Leap Buried Fire

Buried Fire Heroes of the Valley

Heroes of the Valley The Empty Grave

The Empty Grave The Hollow Boy

The Hollow Boy The Last Siege

The Last Siege The Dagger in the Desk

The Dagger in the Desk The Amulet of Samarkand

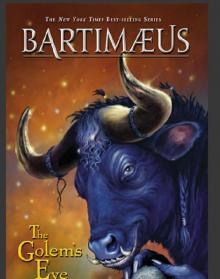

The Amulet of Samarkand The Golem's Eye

The Golem's Eye The Screaming Staircase

The Screaming Staircase The Outlaws Scarlett and Browne

The Outlaws Scarlett and Browne The Ring of Solomon: A Bartimaeus Novel

The Ring of Solomon: A Bartimaeus Novel Lockwood & Co

Lockwood & Co Lockwood & Co: The Screaming Staircase

Lockwood & Co: The Screaming Staircase Bartimaeus: The Amulet of Samarkand

Bartimaeus: The Amulet of Samarkand The Amulet of Samarkand tbt-1

The Amulet of Samarkand tbt-1 Lockwood & Co.: The Creeping Shadow

Lockwood & Co.: The Creeping Shadow The Ring of Solomon

The Ring of Solomon Lockwood & Co. Book Three: The Hollow Boy

Lockwood & Co. Book Three: The Hollow Boy Bartimaeus: The Golem’s Eye

Bartimaeus: The Golem’s Eye