- Home

- Jonathan Stroud

The Ring of Solomon: A Bartimaeus Novel Page 6

The Ring of Solomon: A Bartimaeus Novel Read online

Page 6

6 As well as all this the Ring was said to protect Solomon from magical attack, give him extraordinary personal allure (which possibly explained all those wives cluttering up the place) and allow him to understand the language of birds and animals. Not bad, in short, though the last one isn’t half as useful as you might expect, since when all’s said and done the language of the beasts tends to revolve around: (a) the endless hunt for food, (b) finding a warm bush to sleep in of an evening, and (c) the sporadic satisfaction of certain glands.* Elements such as nobility, humour and poetry of the soul are conspicuously lacking. You have to come to middle-ranking djinn for them. * Many would argue that the language of humankind boils down to this too.

7 It was the guise I’d worn when I was spear-bearer to Gilgamesh, two thousand years before: a tall, beautiful young man, smooth-skinned and almond-eyed. He wore a long wrapped skirt, necklaces of amethyst on his breast and ringlets in his hair, and had about him an air of wistful grace that contrasted pungently with the foul detritus of the kitchen yard. I often used this form in such circumstances. It made me feel better somehow.

8 Solomon’s edicts dictated that ordinary human shapes were maintained at all times outside the palace walls. Animals were forbidden, likewise mythic beasts; grotesque deformities were out too, which was a shame. The idea was to prevent the common people being startled by repulsive sights – such as Beyzer taking a stroll with his limbs on back to front. Or, admittedly, yours truly forgetfully popping out to buy some figs in the guise of a rotting corpse, thus causing the great Fruit Market Terror, fifteen deaths in the associated stampede, and the destruction of half the commercial district. Got my figs dirt cheap, mind, so it wasn’t all bad.

7

His name1 was Khaba, and whatever else he might have been, he was certainly a formidable magician. In origin, perhaps, he was a child of Upper Egypt, the quick-witted son of some peasant farmer toiling in the black mud of the Nile. Then (for this is the way it had worked for centuries) the priests of Ra would have chanced upon him and taken him away to their granite-walled stronghold at Karnak, where quick-witted youths grew up in smoke and darkness, and were taught the twinned arts of magic and amassing power. For a thousand years and more, these priests had shared with the pharaohs control of Egypt, sometimes vying with them, sometimes supporting them; and in the days of the nation’s glory Khaba would doubtless have remained there, and by plot or poison worked his way close to the pinnacles of Egyptian rule. But the throne of Thebes was old and battered now, and a greater light shone in Jerusalem. With ambition gnawing in his belly, Khaba had learned what he could from his tutors, then travelled east to seek employment at the court of Solomon.

Perhaps he had been here many years. But he carried the odour of the Karnak temples still. Even now, as he clambered to the hilltop and stood regarding us in the brightness of the noonday sun, there was something of the crypt about him.

Up until that moment I’d only seen him in the summoning room of his tower, a place of darkness where I’d been in too much pain to assess him properly. But now I saw that his skin had a faint grey cast that spoke of windowless sanctuaries underground, while his eyes were large and roundish, like those of cavern fishes circling in the dark.2 Below each eye a thin, deep weal descended almost vertically across his cheek towards his chin; whether these marks were natural, or had been caused by some desperate slave, was a matter for speculation.

In short, Khaba wasn’t much of a looker. A cadaver would have crossed the street to avoid him.

As with all the strongest magicians, his dress was simple. His chest was bare, his skirt plainly wrapped and unadorned. A long, leather-handled whip of many cords swung from a bone hook at his belt; about his neck, suspended on a loop of gold, hung a black and polished stone. Both objects pulsed with power; the stone, I guessed, was a scrying glass that allowed the magician to view things far away. The whip? Well, I knew what that was, of course. Just the thought of it made me shiver on the sunlit hill.

The row of djinn stood silently as the magician looked us up and down. The big, moist eyes blinked at each of us in turn. Then he frowned and, holding one hand above his eyes to shield them from the glare, looked again at our horns and tails and other extracurricular additions. His hand stole towards the whip, fingers tapped upon the handle for a moment … then fell away. The magician took a short pace back, and addressed us in a soft and chalky voice.

‘I am Khaba,’ he said. ‘You are my slaves and my instruments. I tolerate no disobedience. That is the first thing you need to know. Here is the second thing: you stand on the high hill of Jerusalem, a place held sacred by our master, Solomon. There shall be no frivolity or misbehaviour here on pain of direst penalty.’ Slowly he began to walk to and fro along the line, his shadow trailing long and thin behind him. ‘For thirty years I have sent demons scampering beneath my whip. Those that resisted me I have crushed. Some are dead. Others yet live – after a fashion. None have gone back to the Other Place. Heed this warning well!’

He paused. His words echoed off the palace walls and faded.

‘I notice,’ Khaba continued, ‘that in defiance of Solomon’s edicts, you each flaunt some devilish accessory to your human forms. Perhaps you expect me to be shocked. If so, you are mistaken. Perhaps you think of this pathetic gesture as some kind of “rebellion”. If so, it merely confirms what I already know – that you are too cowed and fearful to try anything more impressive. Keep your horns for today, if it makes you feel better, but be aware that from tomorrow I shall use my essence-flail on any who display them.’

He took the whip in hand and flourished it in the air. Several of us flinched, and eight gloomy pairs of eyes watched the cords flicking to and fro.3

Khaba nodded with satisfaction and returned it to his belt.

‘Where now are those arrogant djinn who caused such trouble to their previous masters?’ he said. ‘Gone! You are docile and obedient, just as you should be. Very well, to your next task. You are brought together to begin work on a new construction project for King Solomon. He wishes a great temple to be built here, an architectural marvel that will be the envy of the kings in Babylon. I have been given the honour of fulfilling the initial phase – this side of the hill must be cleared and made level, and a quarry opened up in the valley below. You will follow the plans I give you, shaping the stones and dragging them up here, before— Well, Bartimaeus, what is it?’

I had raised an elegant hand. ‘Why drag the stones? Isn’t it quicker to fly them up? We could all manage a couple at a time, even Chosroes.’

A djinni with bat ears further up the line gave an indignant squeak. ‘Hey!’

The magician shook his head. ‘No. You are still in the confines of the city. Just as Solomon has forbidden unnatural guises here, you must avoid magical shortcuts and work at human pace. This will be a holy building, and must be built with care.’

I gave a cry of protest. ‘No magic? But this’ll take years!’

The gleaming eyes gazed at me. ‘Do you question my command?’

I hesitated, then looked away. ‘No.’

The magician turned aside and spoke a word. With a dull retort and the faintest smell of rotting eggs, a small lilac cloud billowed into existence at Khaba’s side and hung there, palpitating gently. Lounging in the cloud, its spindly arms behind its head, sat a twirly-tailed green-skinned creature with round red cheeks, twinkling eyes and an expression of impudent over-familiarity.

It grinned at us. ‘Hello, lads.’

‘This is the foliot Gezeri,’ our master said. ‘He is my eyes and ears. When I am not present on the building site, he will inform me of any slackness or deviation from my commands.’

The foliot’s grin widened. ‘They won’t be no trouble, Khaba. Sweet-natured as lambs, the lot of them.’ Sticking a fattoed foot down below its cloud, it kicked once, propelling the cloud a short way through the air. ‘Thing is, they know what’s good for them, you can see that.’

‘I hope so.�

� Khaba made an impatient gesture. ‘Time passes! You must get on with your work. Clear the brushwood and level the hilltop! You know the terms of your summoning: adhere to them always. I want discipline, I want efficiency, I want silent dedication. No backchat, arguments or distractions. Divide yourselves into four work-teams. I shall bring the temple plan out to you presently. That is all.’

And with that he spun upon his heel and began to walk away, the picture of arrogant indifference. Kicking an indolent leg, the foliot guided its cloud after him, making a series of rude faces over its shoulder as it did so.

And still, despite all the provocation, none of us said anything. At my side I heard Faquarl give a kind of strangled snarl under his breath, as if he longed to speak out, but the rest of my fellow slaves were utterly tongue-tied, afraid of retribution.

But you know me. I’m Bartimaeus: I don’t do tongue-tied.4 I coughed loudly and put up my hand.

Gezeri spun round; the magician, Khaba, turned more slowly. ‘Well?’

‘Bartimaeus of Uruk again, Master. I have a complaint.’

The magician blinked his big wet eyes. ‘A complaint?’

‘That’s right. You’re not deaf then, which must be a relief, what with all your other physical problems. It’s my work partners, I’m afraid. They’re not up to scratch.’

‘Not … up to scratch?’

‘Yes. Do try to keep up. Not all of them, mind. I’ve got nothing against …’ I turned to the djinni on my left, a fresh-faced youth with a single stubby brow-horn. ‘Sorry, what was your name?’

‘Menes.’

‘Young Menes. I’m sure he’s a worthy fellow. And that fat one with the hooves over there might be a good worker too, for all I know; he’s certainly packing enough essence. But some of the others … If we’re cooped up here for months on a big job … Well, the long and the short of it is, we just won’t gel. We’ll fight, argue, bicker … Take Faquarl here. Impossible to work with! Always ends in tears.’

Faquarl gave a lazy chuckle, showing his gleaming fangs. ‘Ye-e-es … I should point out, Master, that Bartimaeus is an appalling fantasist. You can’t believe a word he says.’

‘Exactly,’ the hoofed slave put in. ‘He called me fat.’

The bat-eared djinni snorted. ‘You are fat.’

‘Shut up, Chosroes.’

‘You shut up, Beyzer.’

‘See?’ I made a regretful gesture. ‘Bickering. Before you know it we’ll be at each other’s throats. Best thing would be to dismiss us all, with the notable exception of Faquarl, who, despite his deficient personality, is very good with a chisel. He will be a fine and loyal servant for you and work hard enough for eight.’

At this the magician opened his mouth to speak, but was pre-empted by a somewhat forced laugh from the pot-bellied Nubian, who stepped smoothly forward.

‘On the contrary,’ he urged, ‘Bartimaeus is the one you should keep. As you can see, he’s as vigorous as a marid. He is also famed for his achievements in construction, some of which resound in fable to this day.’

I scowled. ‘They don’t at all. I’m hopeless.’

‘Such modesty is typical of him,’ Faquarl smiled. ‘His only drawback is an inability to work with other djinn, who are usually dismissed when he is summoned. But – to his abilities. Surely even in this backwater you will have heard of the Great Flooding of the Euphrates? Well, then. The instigator stands right there!’

‘Oh, it’s just like you to bring that up, Faquarl. That incident was totally over-reported. There was no real harm done—’

The bat-eared Chosroes gave a cry of indignation. ‘No harm? An inundation from Ur to Shuruppak, so that only the flat white rooftops protruded above the waters? It was like the world was drowned! And all because you, Bartimaeus, built a dam across the river for a bet!’

‘Well, I won the bet, didn’t I? Get things in perspective.’

‘At least he can build something, Chosroes.’

‘What? My building projects in Babylon were the talk of the town!’

‘Like that tower you never finished?’

‘Oh come now, Nimshik – that was down to problems with foreign workers.’

My work was done. The argument was going nicely; all discipline and focus had vanished, and the magician was a satisfying shade of purple. All complacency had gone from the foliot Gezeri too, who was gawping like a trout.

Khaba gave a cry of rage. ‘All of you! Be still.’

But it was far too late. Our line had already disintegrated into a bickering melee of shaking fists and jabbing fingers. Tails whirled, horns flashed in the sun; one or two previously absent claws slyly materialized to reinforce their owners’ points.

Now, I’ve known some masters to give up at this juncture, to throw their hands in the air and dismiss their slaves – if only temporarily – just to get a bit of peace. But the Egyptian was made of sterner stuff. He took a slow step backwards, his features twisted, and unhooked the essence-flail from his belt. Clasping it firmly by its handle and shouting out an incantation, he cracked it once, twice, three times above his head.

From each of the whirling thongs emerged a jagged spear of yellow force. The spears stabbed out, impaled us all and snatched us burning into the sky.

Up under the hot sun we swung, higher than the palace walls, suspended on yellow snags of burning light. Down below us the magician spun his arm in looping circles, high and low, faster and faster, while Gezeri hopped and capered in delight. Round we flew, limp and helpless, colliding sometimes with each other, sometimes with the ground. Showers of wounded essence trailed behind us, hung shimmering like oily bubbles in the desert air.

The Gyration ceased, the essence-skewers were withdrawn. At last the magician lowered his arm. Eight broken objects fell heavily to Earth, our edges sloughing like pats of melting butter. We landed on our heads.

The dust clouds slowly settled. Side by side we sat there, wedged into the ground like broken teeth or tilting statues. Several of us were gently steaming. Our heads were half buried in the dirt, our legs sagged in the air like wilting stems.

Not far away, the heat haze shifted, broke, re-formed, and through its fractured strands the magician strode, his long black shadow flowing at his back. Wisps of yellow force still radiated from the flail, snapping faintly, slowly fading. On all the hill this was the only sound.

I spat out a pebble. ‘I think he forgives us, Faquarl,’ I croaked. ‘Look, he’s smiling.’

‘Remember, Bartimaeus – we’re upside-down.’

‘Oh. Right.’

Khaba came to a halt and stared down at us. ‘This,’ he said softly, ‘is what I do to slaves who disobey me once.’

There was a silence. Even I didn’t have much to say.

‘Let me show you what I do to slaves who disobey me twice.’

He held out his hand and spoke a word. A glimmering point of light, brighter than the sun, floated suddenly in the air above his palm. Soundlessly it expanded to become a luminous sphere, cupped by his hand but still not touching it – a sphere that darkened now, like water filled with blood.

Within the sphere: an image, moving. A creature, slow, blind and in great pain, lost in a place of darkness.

Silent, upside-down and sagging, we watched the lost, maimed thing. We watched it for a long time.

‘Do you recognize it?’ the magician said. ‘It is a spirit like you, or was so once. It too knew the freedom of the open air. Perhaps, like you, it enjoyed wasting my time, neglecting the tasks I gave it. I do not recall, for I have kept it in the vault beneath my tower for many years, and it has probably forgotten the details itself. Occasionally I give it certain delicate stimulations just to remind it it is still alive; otherwise I leave it to its misery.’ The eyes blinked slowly round at us; the voice was just as level as before. ‘If any of you wish to become like this, you may annoy me one more time. If not, you will set to work and dig and carve as Solomon commands – and pray, if such a reflex is in your nat

ure, that I may one day permit you to leave this Earth again.’

The image in the sphere dwindled; the sphere fizzled and went out. The magician turned away and headed off towards the palace. His shadow trailed long and black behind him, skipping, dancing across the stones.

None of us said anything. One after another we toppled sideways and collapsed into the dust.

1 His assumed name, I mean – the name by which he was known in his comings and goings about the world. It was meaningless, in truth, a mask beneath which his true nature was protected and concealed. Like all magicians, his birth-name – the key to his power and his most precious possession – had been expunged in childhood, and forgotten.

2 They were unappetizingly moist too, as if he was just about to weep with guilt or sorrow, or in pity for his victims. But did he? Nope. Such emotions were alien to Khaba’s heart and the tears never came.

3Essence-flail: the favoured weapon of the priests of Ra back in the old days of Khufu and the pyramids. Very good at keeping djinn in order. Theban craftsmen still make them, but the best are found in ancient tombs. Khaba’s was an original – you could tell by the handle, which was bound in human-slave skin, complete with faint tattoos.

4 Apart from literally, once or twice, when certain Assyrian priests got so peeved with my cheek they pierced my tongue with thorns and bound me by it to a post in Nineveh’s central square. However, they’d reckoned without the elasticity of my essence. I was able to elongate my tongue sufficiently to retire to a nearby inn for a leisurely drink of barley wine, and subtly trip up several dignitaries as they strutted by.

8

North of Sheba the deserts of Arabia stretched unbroken for a thousand miles, a vast and waterless wedge of sand and stone-dry hills, bordered to the west by the blank Red Sea. To the far north-west, where the peninsula collided with Egypt, and the Red Sea petered out at the Gulf of Aqaba, lay the trading port of Eilat, since ancient times a meeting place of roads and goods and men. To get from Sheba to Eilat, where their spices could be sold at great profit in the old bazaars, the frankincense traders travelled a circuitous route between the desert and the sea, winding through numerous petty kingdoms, paying tolls and fighting off attacks by hill-tribes and their djinn. If all was set fair, assuming their camels remained healthy and they escaped major depredations, the traders could expect to arrive in Eilat after six or seven weeks in a state of considerable exhaustion.

The Leap

The Leap Buried Fire

Buried Fire Heroes of the Valley

Heroes of the Valley The Empty Grave

The Empty Grave The Hollow Boy

The Hollow Boy The Last Siege

The Last Siege The Dagger in the Desk

The Dagger in the Desk The Amulet of Samarkand

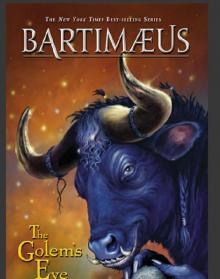

The Amulet of Samarkand The Golem's Eye

The Golem's Eye The Screaming Staircase

The Screaming Staircase The Outlaws Scarlett and Browne

The Outlaws Scarlett and Browne The Ring of Solomon: A Bartimaeus Novel

The Ring of Solomon: A Bartimaeus Novel Lockwood & Co

Lockwood & Co Lockwood & Co: The Screaming Staircase

Lockwood & Co: The Screaming Staircase Bartimaeus: The Amulet of Samarkand

Bartimaeus: The Amulet of Samarkand The Amulet of Samarkand tbt-1

The Amulet of Samarkand tbt-1 Lockwood & Co.: The Creeping Shadow

Lockwood & Co.: The Creeping Shadow The Ring of Solomon

The Ring of Solomon Lockwood & Co. Book Three: The Hollow Boy

Lockwood & Co. Book Three: The Hollow Boy Bartimaeus: The Golem’s Eye

Bartimaeus: The Golem’s Eye