- Home

- Jonathan Stroud

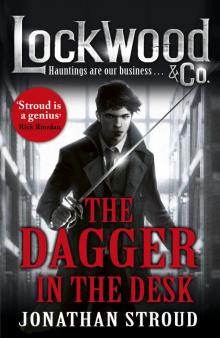

The Dagger in the Desk Page 2

The Dagger in the Desk Read online

Page 2

The fourth door was open. We didn’t need to read its sign to know that this was the one we sought. Its window panel had been smashed; bright shards of glass glinted in our torchlight, and crunched beneath our boots as we entered the room.

Everywhere was evidence of the pupils’ rapid departure the day before: books and pencil cases littering the table; bags and coats lying crumpled on the floor. At the front of the class, the teacher’s chair lay upended. And close by, jutting from the side of the desk that faced the door, we found the object that had so terrified Mr Whitaker.

It was a long, thin-bladed knife. The hilt was wound with leather strips, very old and frayed. Fragments of grey cobwebs hung from it too, swaying slightly in small movements of the air.

‘That’s not an ordinary knife,’ I said. ‘That’s a dagger.’

‘You know what it looks like to me?’ Lockwood said slowly. ‘An old military weapon. If I had to guess, I’d say First World War issue – the kind all soldiers carried.’

‘Well, where’s it come from?’

‘Answer that, and we find our ghost.’ Lockwood straightened. ‘Listen, Lucy – I’m going to double-check further down the corridor. I’m pretty sure there’ll be nothing to find: I think the Source is between here and the library. I’ll be back in a minute, but while I’m gone, just start some readings in the classroom, would you?’

‘Sure.’

He slipped out of the door and was gone into the dark. I scarcely noticed him go. I was too busy staring at the dagger in the desk. One of my Talents, you see, is that of Touch. Sometimes, if I hold an object that has some kind of psychic charge, I feel or hear things associated with its past. Not every time. It doesn’t always work. And if the psychic charge is too strong, it can be uncomfortable or even dangerous for me. But the insights are often useful.

I stared at the dagger and wondered if I should risk it . . .

Of course I should! I was an agent. Taking horrible risks was part of the job description. We might as well have put it on our business cards.

I reached down and placed my fingers on the hilt.

At first there was nothing – nothing but the cool roughness of the leather strips that had been wrapped tightly around the metal. Nothing but the icky-sticky wispiness of the cobwebs trailing against my skin. I closed my eyes, tried to empty out my mind.

And all at once sensations came.

I gasped. I took a sharp breath in. They weren’t nice sensations, and they filled me with a swirling tide of bitterness and fury. There was pain and dull resentment there, and envy too. But most of all there was greed – a hard, tight avarice that lusted after valuable things. Fleeting images came and went: I saw laughing children, school passages and classrooms (old-fashioned, but recognizably the same as the ones we now explored), and (dimly) soldiers struggling in a muddy field. But by far the strongest picture was that of an open box or chest filled with coins, and it brought with it a feeling of dark glee.

I nearly took my hand away then, but suddenly, rising from the past, I saw a face I recognized – a beefy face with enormous side-whiskers. It gazed at me fiercely and seemed to speak. And now I was awash with fear and hate, and I was fleeing through the corridors, trying to get away, trying to reach my secret place . . . A door slammed . . . I was alone and safe! Safe for the moment! And, best of all, I still had my precious—

‘Lucy!’

My eyes snapped open. The voice broke through my trance. I snatched my hand away from the knife and, turning, peered off through the open classroom door and down along the passage. I did so almost blindly. It’s always hard when you’ve used your Talent. Your head’s all woozy, and your senses don’t quite work. Like waking from a dream, it takes you a few moments to come round. Plus it was very dark.

‘Lucy . . .’

Halfway back towards the library, I saw a figure standing, tall and thin. It beckoned to me quickly.

‘Lockwood?’ I felt in my belt for my torch. ‘Is that you?’

The shape beckoned once more; slipped out of sight towards one of the storerooms. By the time I’d stabbed my torch on, it was gone.

‘Lockwood?’ I called again.

No answer. But I’d heard the urgency in the voice, seen the eager beckoning. I hurried out of the classroom and along the corridor. It was very cold out there.

‘Lucy . . .’

No mistake this time. The voice came from behind the door to the store cupboard. I reached out to turn the handle—

A cough sounded right behind me.

I whirled round, shone my torch up. Lockwood stood there – calm, unflustered, one eyebrow elegantly raised.

‘Luce. What are you doing? I thought I told you to stay in the classroom.’

I blinked at him foolishly. ‘Er . . . yes, you did. But didn’t you just call me?’

He looked at me.

‘Didn’t you just beckon me to come?’

‘I did neither. I’ve just been exploring further down the corridor like I said I was going to. As predicted, I found nothing. Because it’s here that the action is. As you’ve just proved. What did you see?’

I shuddered, looked towards the cupboard door. ‘I don’t know. But whatever it was, it wanted me to join it in there.’

Lockwood’s eyes narrowed. ‘Well, perhaps we can oblige it shortly. But only when we’re properly armed. Learn anything in the classroom?’

I took a deep breath. It’s always difficult to express what you get through psychic sensations. It’s hard to put it into words. But this time I didn’t even have a chance to try, because at that moment a loud, shrill and unmistakably George-like scream resounded down the corridor from the library. It echoed off the walls and faded.

Lockwood and I stared at each other, wide-eyed.

‘Oh, you know what George is like,’ Lockwood said. ‘He’s probably dropped an encyclopaedia on his toe.’

Even so, he was already running.

Well, it wasn’t a single encyclopaedia that was the problem, as we discovered when we burst into the library. To aid his reading George had evidently taken a lantern from his bag and set it burning inside the iron circle, and by its flickering light we saw a startling scene. Almost all the books that had been so neatly arranged around the shelves had been ripped out and hurled across the room. They lay scattered every which way, spines up, spines down, pages ruffling and twitching. The only spot free of them was the space inside the iron chains, and it was here that George was crouching, white-faced, hands crossed protectively over his head.

‘I know you’re an avid reader, George,’ Lockwood remarked, ‘but this is a bit messy even for y—’

‘Watch out!’ George’s cry came too late. Even as he spoke, a heavy hardback book struck Lockwood on the side of the head, sending him toppling to the floor. And now a host of others were rising into the air, carried by a random, unseen force. They whizzed this way and that, thumping into walls, bouncing off the windows. I dived to the side: one shot straight past me and crashed against a shelf. All across the room, books were shifting, shelves rattling, chair- and table-legs scraping as they moved across the floor. On the plinth beside the windows, the marble bust of Ernest Potts was shaking violently, as if it were about to burst. I bent down beside Lockwood, who lay on his side, half dazed.

‘I think I know who it is!’ George called. ‘He hates Potts – that’s why he’s come back and—’ He ducked as a book spun viciously past his nose.

I looked desperately around the room. The violence of the attack was escalating. More and more objects were beginning to move.

First things first. I needed to get Lockwood into the circle. I grabbed him by the arms, and began to pull him across the room. It wasn’t easy: he’s bigger than me and was carrying a lot of kit, and the whirling books that struck me made things worse. George jumped over the chains and sprang to help me. He bent towards Lockwood. As he did so, there was a disturbance in the air behind him. Glimmering threads of other-light appeared. They gr

ew and melded, fusing into a tall thin shape that reached for George.

I let go of Lockwood’s hand, tore my rapier from my belt and swung it over George’s head. The iron blade cut straight through the glowing form. The figure vanished. The rushing air went still. All across the library, books dropped crashing to the ground.

A moment later we’d got Lockwood inside the chains, and were sprawled there, gasping. Lockwood was sitting up now, with a bad bruise on his temple. He still looked a trifle dazed.

‘So you think you know the identity of our ghost, George?’ I said, once I could speak.

‘Yeah,’ George said. ‘I reckon. I found it in a history of the school. His name was Harold Roach, and he was caretaker here, almost a hundred years ago. He’d been badly wounded in the First World War – one arm shot off, and injured in the leg as well. So he was an unlucky guy, but it sounds like he was already a nasty piece of work. He used to stalk around the school terrorizing the pupils. Apparently he always carried an old army knife, and he’d wave it at any kid who crossed him, threatening to cut off their ears.’

‘Ah, the great British education system,’ Lockwood said. ‘Made us what we are.’

‘There was also speculation that he used to steal money from the school funds,’ George went on, ‘though nothing was ever proved. Anyway, it all changed when this Ernest Potts became headmaster.’ He jerked his thumb towards the bust beside the window. ‘He wasn’t having any truck with caretaker Roach. Seems he confronted him – more or less accused him of nicking the cash. Roach denied it, but when Potts threatened to bring in the police, the man promptly slipped away and vanished. He was never found. Everyone assumed he’d scarpered with the money.’

‘Or else,’ Lockwood said softly, ‘he’s still here.’ There was a brief silence.

‘That all fits in with what I sensed too,’ I said. I told them about my experiences with the dagger and, briefly, the figure I’d seen in the corridor. ‘I think he hid somewhere in the school – the place where he was stashing the money he stole. Maybe he did plan to slip away with it, but for some reason was prevented from doing so. As for where he is, I think we know the answer to that too.’

‘There are two storerooms, George,’ Lockwood said. ‘One’s full-size, the other’s little more than a cupboard: it doesn’t go far back at all. Lucy saw the ghost go inside. There’s plenty of space behind it for a hidden room.’

George nodded. ‘That’s it, then. That’s where Harold Roach will be.’ He reached wearily for his bag. ‘So let’s get on with it, shall we – before his ghost comes back.’

Soon afterwards we had assembled in the passage, ready for the final part of the investigation. We’d checked our kit. We had our rapiers, salt-bombs and canisters of iron. We had our chains. We had our explosive magnesium flares that shouldn’t really be used in confined spaces on account of setting fire to things. We had our bags of silver seals to use on the Source when we found it. Yep, we were all sorted, raring to go. Aside, that is, from Lockwood’s continued grogginess, and my sense of overwhelming fear whenever I looked at those storeroom doors. I remembered that little wheedling voice, calling me in.

George hitched up his belt, which had sagged slightly under his tummy. ‘Right,’ he said. ‘You’re clearly not up to this, Lockwood, and Lucy’s understandably edgy after what happened to her out here. So how about I go in first?’

I looked at him askance. ‘Really? Sure you’re OK with that?’ George isn’t usually the one who leads the way.

He chuckled. ‘Trust me.’

‘Nice and quiet, then, George,’ Lockwood said.

George raised his rapier. He pulled at the left-hand door – the one to the larger storeroom. It swung slowly open. He aimed his torch inside. His circle of light passed over vacuum cleaners, paper towels, tins of paint . . . everything exactly as before. George stepped into the room. Lockwood and I followed. We were calm, silent and professional, moving with panther-like stealth.

‘There,’ George whispered. ‘Nothing to worry about so far.’ He swung his torch to the side, gave a yell like a howler monkey, and leaped back a clear metre, colliding with Lockwood and me. We all careered back into a shelf. There was an almighty crash and splintering as the shelf snapped and we toppled to the ground. Paint tins and toilet rolls bounded and trundled out across the floor.

We struggled to our feet. Three frantic torches spun light around the room.

‘Oh,’ George said. ‘It’s all right. Relax, everyone. It was just a mop.’

‘What?’ Lockwood and I both stared at him.

‘I thought it was a very thin ghost. But it’s only a mop. Look! It’s got the floppy bit at the top. I ask you. Who does that? Who stores a mop upside-down?’

‘George—’ I began.

‘Wait!’ Lockwood was staring at the wall. ‘Look at the panelling! It’s floor to ceiling here! Everywhere else in the school it only goes halfway up. Behind this wall is the store cupboard, which we know only goes back a few feet. So these panels would be the perfect place for a hidden door.’

George frowned. ‘We’ve got crowbars. Let’s smash our way in.’

‘Finding the lever or switch would be easier.’ Lockwood placed his hands on the panelling and instantly jerked them away. ‘Ow – it’s cold!’

Even as he said this, we noticed we could see our breath-plumes again. That’s never a good sign. Nor, to be honest, is the sound of dragging footsteps, or the rattling of keys, both of which I could suddenly hear again, not very far away.

‘He’s back,’ I whispered. ‘I can hear him coming.’

Lockwood was running his fingers along the edges of the panelling. ‘Didn’t take him long,’ he said. ‘OK. George, give me a hand searching the wall. Lucy, do me a favour and just have a quick look in the corridor, would you?’

I peeped out. In the direction of the library, all was dark. In the direction of the classroom, a pale haze of other-light had gathered in the centre of the passage. At its heart I saw a tall thin figure, limping in our direction. The apparition was faint, but getting stronger, and I could already see the ragged clothes, the dragging leg, the loosely hanging arm . . . Also the cold metallic shimmer of a dagger, held outstretched in bony fingers.

I ducked back into the storeroom, where Lockwood and George were tapping at the panels. ‘Bad news,’ I said hoarsely.

Lockwood didn’t look up. ‘How long have we got?’

‘I’d say about thirty seconds.’

‘OK.’ Lockwood pressed a discoloured portion of panel speculatively. Nothing happened. ‘Lucy,’ he said, ‘George and I are going to need a little longer than that. Two minutes – maximum three. Think you can delay our friend Harold that long?’

I turned back to the door. ‘I’ll see what I can do.’

Out in the corridor, the ragged, limping figure had drawn much closer; it had passed the toilets and was level with the other storeroom. Harsh cold radiated from its glow, and the malevolence of its purpose struck me like a solid thing. My head felt suddenly woozy, my limbs listless, heavy as concrete. The thud and drag of each maimed footfall beat like a drum against my ears. I could see the glittering of the knife.

All of which meant it was high time I did something. I flicked my coat aside, plucked a salt-bomb from my belt and threw it hard and fast, so that it burst on the floor just below the glowing form. The brittle plastic snapped; salt spattered out across the passage, flaring bright green as it hit the ectoplasm. The apparition flexed, distorting like an image seen in water, and blinked out – only to reappear instantly, some distance further away.

I ducked back into the storeroom. ‘How’s it going?’

Lockwood and George were crouched beside the wall, their attention focused on one particular panel that looked no different to the rest. ‘Found it,’ Lockwood said. ‘Little clasp hidden at the base. Think it opens inwards, but it’s hellish stiff. Sixty seconds.’

‘Right.’

I took a magnesium flare fro

m my belt, hefted it in my hand and went back out into the passage. As I did so, something flashed past me, close enough to waft my fringe across my face. I looked – and saw the dagger, still vibrating, buried hilt-deep in the plaster of the wall. And now the pale, thin figure was rushing up the corridor, legs trailing, rags flapping, single arm reaching out to clasp me.

Well, it had annoyed me now. I lobbed the flare.

A blast of magnesium fire, peppered with filaments of burning salt and iron, is white enough and bright enough to momentarily blind the living, as well as do considerable damage to the dead. So I screwed up my eyes, and waited for the initial surge of heat to fade. And when I looked again, pockets of white flames were licking up across the passage floor, and the walls were pebble-dashed with smouldering pin-sized burns. The ghost itself had vanished.

I dived back into the storeroom, where Lockwood and George seemed to be in an almost identical position. ‘How’s it going now?’

‘George has got blisters, and I’ve got my hand stuck.’

‘I was thinking about the door.’

‘It’s jammed. Either rusted, or something heavy on the other side.’

‘Help give it a shove, can you?’ George gasped. ‘Three of us might do the trick.’

I looked behind me. The silvery light was fading: already the fires were dying down. ‘I used a flare,’ I said. ‘It’s flummoxed him, but he’ll be back any moment. He’s strong.’

‘I know,’ Lockwood said, ‘but we’ve got to get this open. Your weight might make the difference, Luce.’

‘Exactly what are you saying?’ But I ranged myself alongside them, and took the strain. I could see the hidden door now, a faint dark outline in the wood. Lockwood’s fingers were prising at one edge; George was heaving at its base. When I pushed, I felt the panel move.

The Leap

The Leap Buried Fire

Buried Fire Heroes of the Valley

Heroes of the Valley The Empty Grave

The Empty Grave The Hollow Boy

The Hollow Boy The Last Siege

The Last Siege The Dagger in the Desk

The Dagger in the Desk The Amulet of Samarkand

The Amulet of Samarkand The Golem's Eye

The Golem's Eye The Screaming Staircase

The Screaming Staircase The Outlaws Scarlett and Browne

The Outlaws Scarlett and Browne The Ring of Solomon: A Bartimaeus Novel

The Ring of Solomon: A Bartimaeus Novel Lockwood & Co

Lockwood & Co Lockwood & Co: The Screaming Staircase

Lockwood & Co: The Screaming Staircase Bartimaeus: The Amulet of Samarkand

Bartimaeus: The Amulet of Samarkand The Amulet of Samarkand tbt-1

The Amulet of Samarkand tbt-1 Lockwood & Co.: The Creeping Shadow

Lockwood & Co.: The Creeping Shadow The Ring of Solomon

The Ring of Solomon Lockwood & Co. Book Three: The Hollow Boy

Lockwood & Co. Book Three: The Hollow Boy Bartimaeus: The Golem’s Eye

Bartimaeus: The Golem’s Eye