- Home

- Jonathan Stroud

The Ring of Solomon Page 15

The Ring of Solomon Read online

Page 15

‘Really? Well, I’m used to complex stuff, so I could follow what you said just now. But I warn you, round this part of the world they wouldn’t be able to cope with much apart from that bit about your unworthy bottom.’

Asmira blinked. ‘My unworthy heart.’

‘That too, I should think. Well now, in answer to your questions, you don’t have to worry any more. Faquarl’s gone to fetch our master, who will doubtless escort you to Jerusalem as you requested. If, in return, you could intercede with him and win our freedom, we would be very much obliged. Lately our servitude under Solomon has been getting rather grating.’

Asmira’s heart quickened. ‘Solomon himself is your master?’

‘Technically no. In practice, yes.’ The young man scowled. ‘It’s complicated. Anyway, the magician will be here soon. Perhaps you could spend the time rehearsing a few gushing tributes on my behalf.’

Whistling, the demon moved off slowly amongst the scattered debris of the camel-train. Asmira watched it, thinking hard.

Ever since the adrenaline of battle had ebbed inside her, she had been fighting to keep control of herself and her surroundings. To begin with, shock had fogged her mind – shock at the sudden ambush, at the destruction of the men with whom she had travelled for so many days, at the hideous vigour of the lizard demon and the way it had withstood her Ward. At the same time she had had to face down Solomon’s spirits, concealing the fear she felt for them. This had not been easy, but she had succeeded. She had survived. And now, as she observed the demon, she felt a sudden fierce surge of hope. She was alive, and her mission was before her! Not only had disaster been averted; Solomon’s servants were actually going to take her straight to him! In just two nights’ time, the attack on Sheba would come. Such speed might make all the difference.

Some way off, the demon was pacing back and forth, looking at the sky. It had seemed reasonably talkative, if somewhat proud and prickly; perhaps she should converse with it a little more. As a slave of Solomon it would know many things about the king, about his personality, his palace and – possibly – the Ring.

With a brisk movement she jerked the reins. The camel folded its forelegs and tilted forwards, so that it knelt upon the sand. Then it folded its rear ones too. Now it sat; Asmira swung herself off the couch and dropped lightly to the ground. She examined her singed riding cloak briefly, and smoothed it down. Then, leather bag in hand, she walked towards the demon.

The winged youth was lost in thought. Sunlight glinted on the bright, white wings. For a moment Asmira was conscious of its stillness, and the look of melancholy on the quiet face. She wondered what it saw before its eyes. With annoyance she realized her limbs were shaking.

It glanced at her as she approached. ‘Hope you’ve thought of some good adjectives for me. “Ferocious”, “zealous” and “awe-inspiring” all trip off the tongue nicely, I find.’

‘I’ve come to talk with you,’ Asmira said.

The dark brows angled. ‘Talk? Why?’

‘Well,’ she began, ‘it’s not often I have a chance to speak with such an exalted spirit as you, particularly one who saved my life. Of course I have often heard tell of the great beings who raise towers in a single night, and bring rain upon the famished lands. But I never thought I would actually speak with one so noble and gracious, who—’ She stopped; the youth was smiling at her. ‘What?’ she said.

‘This “exalted spirit” thinks you want something. What is it?’

‘I hoped your wisdom—’

‘Hold it,’ the demon said. Its black eyes glittered. ‘You’re not talking to some half-baked imp here. I’m a djinni, and a pretty eminent one at that. A djinni, moreover, who built the walls of Uruk for Gilgamesh, and the walls of Karnak for Rameses, and a good many other walls for masters whose names are long forgotten. Solomon the Great is in fact only the latest in a long line of exalted kings to rely heavily on my services. In short, O Priestess of distant Himyar,’ the young winged man went on, ‘I’ve a high enough opinion of myself already not to need any extra flattery from you.’

Asmira felt the colour come rushing to her cheeks. Her fists clenched against her side.

‘Got to get these little things sorted out, haven’t we?’ the djinni said. It winked at her, and leaned casually back against a rock. ‘Now, what is it you wanted?’

Asmira regarded it. ‘Tell me about the Ring,’ she said.

The djinni gave a start. Its elbow slid sideways off the rock, and it was only with a bit of hasty scrambling that it avoided toppling out of view. It adjusted its wings with much ruffling of feathers, and stared at her. ‘What?’

‘I’ve never been to Jerusalem before, you see,’ Asmira said artlessly, ‘and I’ve heard so many wonderful tales of great King Solomon! I just thought that since you were so eminent and so experienced, and since Solomon relies so heavily upon you, you might be able to tell me more.’

The djinni shook its head. ‘Flattery again! I keep telling you …’ It hesitated. ‘Or was it sarcasm?’

‘No, no. Of course not.’

‘Well, whichever it was,’ the young man growled, ‘let’s have less of it, or, who knows, I might just go along with Faquarl’s little suggestion.’

Asmira paused. ‘Why, what was Faquarl’s little suggestion?’

‘You don’t want to know. As to the object to which you refer, I know you’re only a simple girl from the backside of Arabia, but surely even there you must have heard—’ It looked cautiously up and down the gorge. ‘The point is, in Israel it’s best not to discuss certain subjects openly, or indeed at all.’

Asmira smiled. ‘You seem fearful.’

‘Not at all. Just prudent.’ The winged youth seemed out of sorts now, and scowled up at the dark blue sky. ‘Where’s Khaba got to? He should have been here long since. That fool Faquarl must have got lost or something.’

‘If Faquarl’s the name of the other djinni,’ Asmira said lightly, ‘then your name—’

‘Sorry.’ The djinni held up a resolute hand. ‘I can’t tell you that. Names are powerful things, both in the keeping and the losing. They should never be bandied around, either by spirit or human, since they are our deepest, most secret possessions. By my name I was created long ago – and he who learns it has the key to my slavery. Certain magicians undertake great trials for such knowledge – they study ancient texts, decipher the cuneiform of Sumer, risk their lives in circles to master spirits such as me. Those who have my name bind me in chains, force me to cruel acts, and have done for two thousand years. So you can perhaps understand, O maiden of Arabia, why I take good care to ensure my name is kept safe from others that I chance to meet. Do not ask me again, for it is forbidden knowledge, sacrosanct, secure.’

‘So it’s not “Bartimaeus” then?’ Asmira said.

There was a silence. The djinni cleared its throat. ‘Sorry?’

‘Bartimaeus. That’s what your friend Faquarl kept calling you, anyway.’

There was a muttered curse. ‘I think “friend” is putting it a trifle strongly. That idiot. He would insist on having a row in public …’

‘Well, you keep using his name too,’ Asmira said. ‘Besides, I’m going to need to know your name if I’m to intercede with your master, aren’t I?’

The djinni made a face. ‘I suppose so. Well, let me ask a question now,’ it said. ‘What about you? What’s your name?’

‘My name is Cyrine,’ Asmira said.

‘Cyrine …’ The djinni looked dubious. ‘I see.’

‘I am a priestess of Himyar.’

‘So you keep saying. Well, “Cyrine”, why all this interest in dangerous things, like small pieces of golden jewellery we can’t discuss? And what exactly are these “great matters” that bring you to Jerusalem?’

Asmira shook her head. ‘I cannot say. My queen forbids me to discuss them with anyone but Solomon, and I have taken a sacred vow.’

‘Aren’t we prim and proper, all of a sudden?’ the demon s

aid. It regarded her sourly for a moment. ‘Strange that your queen should have sent a lone girl on such an important mission … Then again, that’s queens for you. They get ideas. You should have heard Nefertiti when the mood was on her. So …’ it went on idly, ‘Himyar. Never been, myself. Pleasant spot, is it?’

Asmira had not been to Himyar either and knew nothing about it. ‘Yes. Very.’

‘Got mountains, I suppose?’

‘Yes.’

‘Rivers and deserts and things?’

‘Lots.’

‘Cities?’

‘Oh, a few.’

‘Including the Rock City of Zafar, delved straight into the cliffs?’ the demon said. ‘That’s in Himyar, isn’t it? Or am I wrong?’

Asmira hesitated. She sensed a trap and didn’t know the answer that would avoid it. ‘I never discuss particularities of my kingdom with an outsider,’ she said. ‘Cultural reticence is one of the traditions of our people. But I can discuss Israel and will do so gladly. You know King Solomon and his palace well, I assume?’

The winged youth was gazing at her. ‘The palace, yes … Solomon, no. He has many servants.’

‘But when he summons you—’

‘His magicians summon us, as I think I’ve said. We serve their will, and they serve Solomon’s.’

‘And they are happy to serve him because of the—’ This time Asmira did not say the word. Something of Bartimaeus’s trepidation had infected her too.

The djinni spoke shortly. ‘Yes.’

‘So you are all in thrall to it?’

‘I and countless others.’

‘So why do you not destroy it? Or steal it?’

The djinni gave a noticeable jump. ‘Shh!’ it cried. ‘Will you keep your voice down?’ With hasty movements it craned its neck back and forth, peering along the gorge. Asmira, reacting to its agitation, looked too, and for a moment thought the blue shadows of the rocks seemed rather darker than before.

‘You do not talk about the object in such terms,’ the djinni glowered. ‘Not here, not anywhere in Israel, and certainly never in Jerusalem, where every second alley cat is one of the great king’s spies.’ It rolled its eyes to the skies and continued quickly. ‘The object to which you refer,’ it said, ‘is never stolen because he who wears it never takes it off. And if anyone even thinks of trying anything in that regard, that same aforesaid person just twizzles the object on his finger and – pop! – his enemies end up like poor Azul, Odalis or Philocretes, to mention but three. That is why no one in their right mind dares defy King Solomon. That is why he sits so vain and untroubled upon his throne. That is why, if you wish to live to undertake these “great matters” you hint at, you will avoid loose talk and curb your curiosity.’ It drew a deep breath. ‘You’re all right with me, Priestess Cyrine from Himyar, for I despise those who hold me captive, and will never alert them even if something – or someone’ – here it looked at her directly, and raised its eyebrows again – ‘arouses my deep suspicions. But I am afraid you will find that others do not share my fine moral character.’ It pointed to the north. ‘Particularly that lot,’ it said. ‘And, needless to say, you’ll find the human is the worst of all.’

Asmira looked where Bartimaeus pointed. A group of distant flecks was fast approaching, dark against the evening sky.

18

Perhaps, if the djinni had not alerted her, Asmira might first have taken the objects in the sky for a flock of birds. If so, her error would not have lasted long. To begin with they were nothing but black dots – seven of them, one slightly larger than the rest – flying in close formation high above the desert hills. But then those dots grew rapidly, and soon she saw the wisps of coloured light that danced along their rushing surfaces, and the heat haze that shivered in their slipstream.

In moments they had dropped to begin the descent towards the gorge, and now she perceived that the fleeting wisps of colour were darts of flame that made each object flash golden in the dying light – all save the largest and most central, which remained coal-black. Closer still they came; now Asmira caught the movement of their wings and heard the distant thrumming noise they made, a sound which quickly swelled to fill her ears. Once, as a little child, she had watched from the palace roof a locust plague descend upon the water meadows below the walls of Marib. The roaring that she heard now was like that distant insect storm, and brought similar apprehension.

The formation dropped below the level of the cliffs and came towards her, following the road. It moved at great speed; with its passing, clouds of sand were sucked into the air, curling out against the hillsides, filling the gorge behind. And now Asmira could see that six of the seven objects were demons, winged, but in human shapes. The seventh was a carpet carried by yet another demon; sitting on this carpet was a man.

Asmira stared at him, at his entourage, at the onrushing display of casual power. ‘Surely,’ she whispered, ‘this is Solomon himself …’

Beside her, the djinni Bartimaeus grunted. ‘Nope. Guess again. This is just one of Solomon’s seventeen master magicians, though perhaps the most formidable of them all. His name is Khaba. I say again, beware of him.’

Sand swirled, the wind howled, giant iridescent wings slowed their beating; six demons halted in mid-air, hovered briefly, dropped lightly to the road. In their centre, the seventh shrugged the carpet off its shoulders onto its great spread arms; bowing low, it retreated backwards, leaving the carpet hanging unsupported a few feet above the ground.

Asmira stared at the silent row of demons. Each wore the body of a man seven or eight foot tall. Save for the one named Faquarl (still stubbornly stocky, bull-necked and pudgy round the waist, and scowling as it looked at her), all were muscular, athletic, dark of skin. They moved gracefully, deftly, confident in their supernatural strength, like minor gods let loose upon the Earth. Their faces were beautiful; their golden eyes gleamed in the dimness of the gorge.

‘Don’t get too worked up,’ Bartimaeus said. ‘Most of them are idiots.’

The figure on the carpet sat motionless, straight-backed, cross-legged, hands folded calmly in his lap. He wore a hooded cloak, clasped tight about him to protect his body from the rigours of the upper air. His face was shadowed, his legs covered in a rug of thick black fur. His long, pale hands were the only part of him exposed; now they unclasped, thin fingers snapped, a word was spoken in the depths of the hood. The carpet dropped to Earth. The man removed the furs and, with a single fluid movement, sprang to his feet. Stepping off the carpet, he walked towards Asmira swiftly, leaving his group of silent demons behind him.

Pale hands pushed back the hood; a mouth stretched wide in welcome.

To Asmira the magician’s appearance was almost more disturbing than that of his slaves. As if in a dream she saw two big, moist eyes, deep scars notched upon his ashen cheeks, thin smiling lips as tight as gut-strings.

‘Priestess,’ the magician said softly. ‘I am Khaba, Solomon’s servant. Whatever sorrows and terrors have beset you shall be no more, for you are come into my care.’ He inclined his bald head towards her.

Asmira bowed likewise. She said, ‘I am Cyrine, a priestess of the Sun in the land of Himyar.’

‘So my slave informed me.’ Khaba did not look back at the line of djinn; Asmira noticed that the burly demon had folded its arms and was regarding her sceptically. ‘I am sorry that I have kept you waiting,’ the magician continued, ‘but I was a great distance away. And, of course, I am all the more sorry that I was not able to prevent this … atrocious attack upon you.’ He waved a hand at the desolation all around.

Khaba stood rather closer to her than Asmira would have liked. He had a curious odour about him that reminded her of the Hall of the Dead, where the priestesses burned incense to the memory of all mothers. It was sweet, pungent and not entirely wholesome. She said, ‘I am grateful to you even so, for your servants saved my life. One day soon, when I return to Himyar, I will see to it that you benefit from the gratitude of my queen.�

��

‘I regret I am not familiar with your land,’ the magician said. The smile upon his face did not alter; the big eyes gazed into hers.

‘It is in Arabia, east of the Red Sea.’

‘So … not far from Sheba, then? It is a curious fact that all the lands thereabouts seem to be ruled by women!’ The magician chuckled at the quaintness of the notion. ‘My birthplace, Egypt, has occasionally flirted with such things,’ he said. ‘It is rarely a success. But, Priestess, in truth I can claim no honour for saving you. It was my king, great Solomon himself, who demanded that we clear the region of these outlaws. If you owe thanks to anyone, it is to him.’

Asmira gave what she hoped was a charming smile. ‘I would wish to give that thanks in person, if I can. Indeed, I travel to Jerusalem on royal business, and crave an audience with Solomon.’

‘So I understand.’

‘Perhaps you could assist me?’

Still the smile remained fixed, still the eyes gazed at her; Asmira had not yet seen them blink. ‘Many wish audience with the king,’ the magician said, ‘and many are disappointed. But I think your status and – if I may say so – your great loveliness will commend you to his attention.’ With a flourish he turned aside, looked back towards his slaves. The smile vanished. ‘Nimshik! Attend to me!’

One of the great entities scampered forward, grimacing.

‘You shall be in charge of the other slaves,’ Khaba said, ‘with the exception of Chosroes, who carries me as before. We will escort this lady to Jerusalem. Your tasks, Nimshik, are as follows. You will clear the road of the corpses and the debris. Bury the fallen, burn the camels. If there are further survivors, you will treat their wounds and bring them to the Gate of the People at the palace – along with any such goods or animals that remain intact. You understand?’

The hulking figure hesitated. ‘Master, Solomon forbids—’

‘Fool! The brigands are destroyed; you will have his permission to return. When all is done, await me on the roof of my tower, where I shall issue new instructions. If you disappoint me in any of this, I will skin you. Be off!’

The Leap

The Leap Buried Fire

Buried Fire Heroes of the Valley

Heroes of the Valley The Empty Grave

The Empty Grave The Hollow Boy

The Hollow Boy The Last Siege

The Last Siege The Dagger in the Desk

The Dagger in the Desk The Amulet of Samarkand

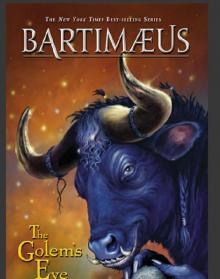

The Amulet of Samarkand The Golem's Eye

The Golem's Eye The Screaming Staircase

The Screaming Staircase The Outlaws Scarlett and Browne

The Outlaws Scarlett and Browne The Ring of Solomon: A Bartimaeus Novel

The Ring of Solomon: A Bartimaeus Novel Lockwood & Co

Lockwood & Co Lockwood & Co: The Screaming Staircase

Lockwood & Co: The Screaming Staircase Bartimaeus: The Amulet of Samarkand

Bartimaeus: The Amulet of Samarkand The Amulet of Samarkand tbt-1

The Amulet of Samarkand tbt-1 Lockwood & Co.: The Creeping Shadow

Lockwood & Co.: The Creeping Shadow The Ring of Solomon

The Ring of Solomon Lockwood & Co. Book Three: The Hollow Boy

Lockwood & Co. Book Three: The Hollow Boy Bartimaeus: The Golem’s Eye

Bartimaeus: The Golem’s Eye